Dopamine-driven Design — an essay on addictive behavioural patterns in modern user interfaces.

Topics

Thoughts, ResearchIntroduction

We’ve all heard someone say ‘just one more game’, or ‘just one more minute’ when playing a game or scrolling through an app. What seem like innocent comments — one more minute can’t hurt, right? — are usually the result of a multitude of addiction-inciting behavioural patterns. Say you’re scrolling through your Twitter timeline on your phone. What’s one more swipe? What’s checking out one more profile or leaving one more nagging comment under some wit’s tweet? This is where the problem starts to show.

One more swipe

Humans like you and me are great at relativising information. We’re able to quickly and effortlessly compare matters and see how much they affect us. In the grand scheme of things, scrolling through Instagram for a little too long does not kill you. “Duh”, you say, “a scroll takes a mere second. What’s the issue?”. I’ll tell you. Our mental modal of time and effort, weighed against the personal gain of that extra swipe, post, video, or game is skewed.

We keep telling ourselves one more swipe can’t hurt, one more post isn’t a problem and one more game is just one more round of fun. However, if you look a bit more closely, you’ll see most apps and games nowadays try to influence your behaviour by adding ‘juice’. Juice is a term that, in its simplest form, means: ‘extra bells and whistles’. Look at most mobile games. They all feature a reward system. They all offer some harder-to-get rewards that either take a lot of time to wait or grind, or can be bought with some made-up currency that costs real money.

Non-rational advertising

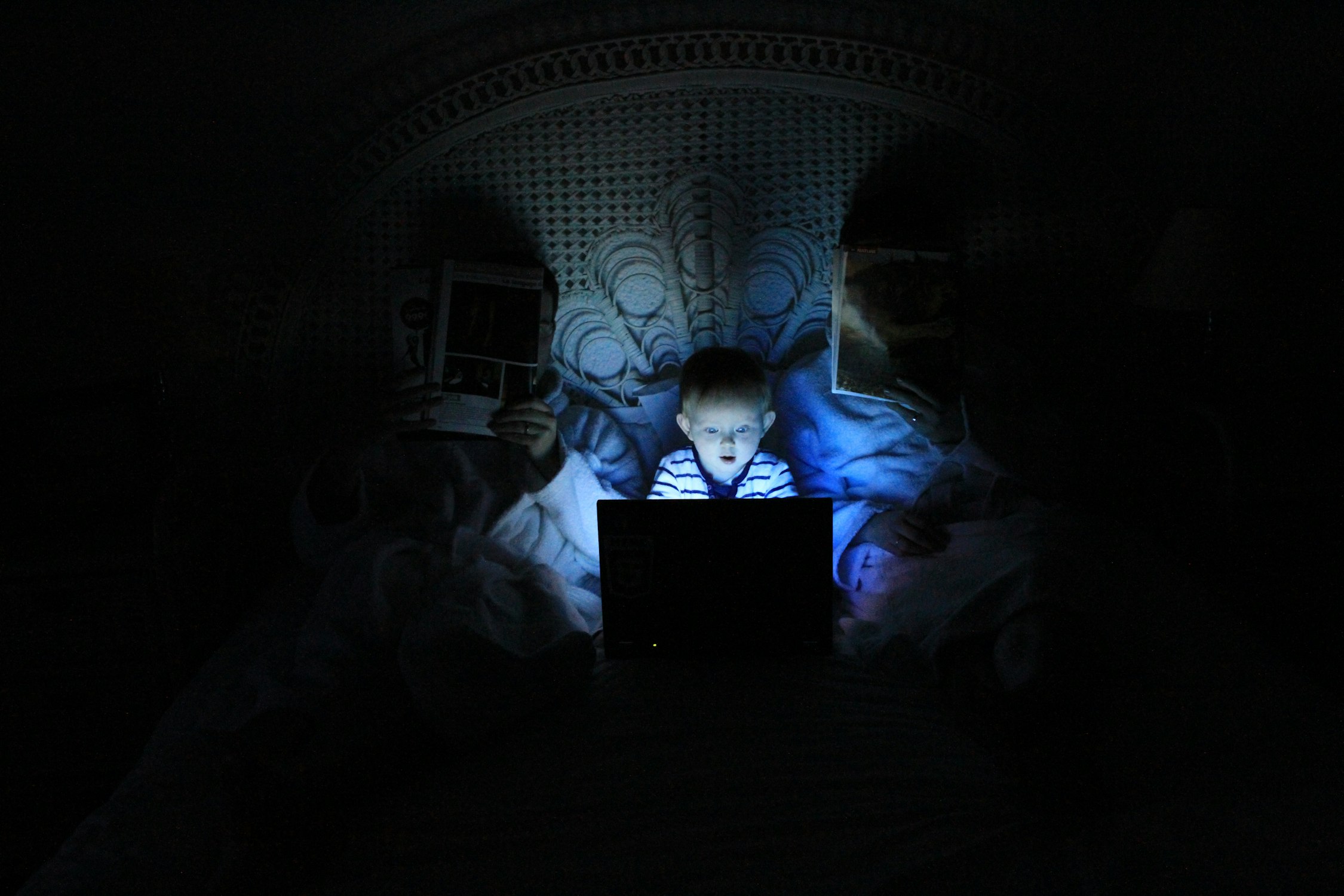

Most of these apps are especially tailored to kids, because they have little to no concept of the value (or lack thereof) of these in-app items. To them, it seems like a big shiny treasure chest must be worth a lot. So they spend a lot of time glaring at their phones, doing nearly nothing. According to a study done in 2016, [citation needed] another large group of kids ask their parents to buy in-game items to speed things up. These items can cost anywhere between €0.99 and €99+. Generally speaking though, they are about the same price as a new app (which usually costs €0.99-€2.99), so it’s a no-brainer for the parents.

Addiction as a marketing strategy

We’ve all been there. We’ve all played an addictive game, like Angry Birds or Candy Crush, and felt the urge to buy some extra lives or extra moves to get that next level. But it’s not just the games themselves that are addictive. Most apps are designed to urge you to keep coming back for more. In most cases, this urge is reinforced by either external rewards (like seeing your favourite celebrity on Instagram) or internal rewards (like feeling good when I finish that level).

The problem is that addiction is not only a problem of the person suffering from it. It affects the people around them, too. The friend who spends hours and hours on Clash of Clans, the mother who spends the whole night on a Candy Crush binge, the father who spends the whole day on the golf course. The people around them may not suffer from the same addiction, but they suffer from the same problem of not getting enough out of their lives.

They suffer from the same problem of losing themselves to addiction.

My point is that whether it’s an app, a game or a movie, the addictive nature of the digital world is not a problem entirely confined to the person suffering from it. It’s a problem that affects all of us. We all have to decide whether we want to be someone who is addicted to a game or an app, or someone who is addicted to something more meaningful, like being a good parent or a good friend.

…but I’m a gamer!

Let’s face it: the digital world has a lot to offer. You can learn languages, play games, chat with friends, share photos and… well, you can also learn how to be addicted. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

I’m a gamer. Or at least I’ve been one. I’ve been playing games since I was young. I started with the Nintendo DS, moved on to the Wii, and then went down the Switch path. I’ve spent countless hours playing games and I’ve spent the same amount of hours writing, playing music, developing and designing. I love games. But I’m not addicted to them.

I’m addicted to doing something in a meaningful way. I’m addicted to learning. I’m addicted to solving problems. I’m addicted to working. I’m addicted to being useful. I’m addicted to having a purpose. I’m addicted to creating new things. I’m addicted to improving myself. I’m addicted to helping others. I’m addicted to achieving things.

I’m not addicted to a game, an app or a movie. I’m addicted to life. I’m addicted to being productive. I’m addicted to being a good person. I’m addicted to having a healthy relationship with my family, my friends and myself. I’m addicted to each day being better than the last. I’m addicted to becoming a better version of myself.

I’m addicted to living.

The difference is that I don’t let my addiction to any of these things consume me. I don’t let it make me do something that I’d later regret. I don’t let it stop me living a fulfilling life. I don’t let it take over my life.

I don’t let it define me.

Afterthought

In a world filled with quick-money-makers and surveillance capitalism, addictive money machines in the form of mobile games are just one ingredient of this messy soup we call the internet. As designers and creators, I think it’s our duty to think conciously about how engaging (and by extension, addictive) we make the stuff we create. It’s okay for customers users us humans not to be engaged 24/7.

We should all strive to create more inclusively, ethically and most importantly: humanely. We’re made of flesh and blood. Emotions.

That’s all for now.